Students at NYU Prague respond to Ukrainian conflict

March 3, 2014

Czech Republic President Milo Zeman expressed his disapproval of Russian military action in Ukraine on March 1, comparing the potential consequences of troop mobilization to the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia by Soviet and Warsaw Pact troops.

Despite warnings from U.S. government officials, Russian President Vladimir Putin mobilized troops in the Crimean Peninsula on Saturday. In response, Ukrainian troops were placed on high alert the next day while NATO commenced an emergency meeting.

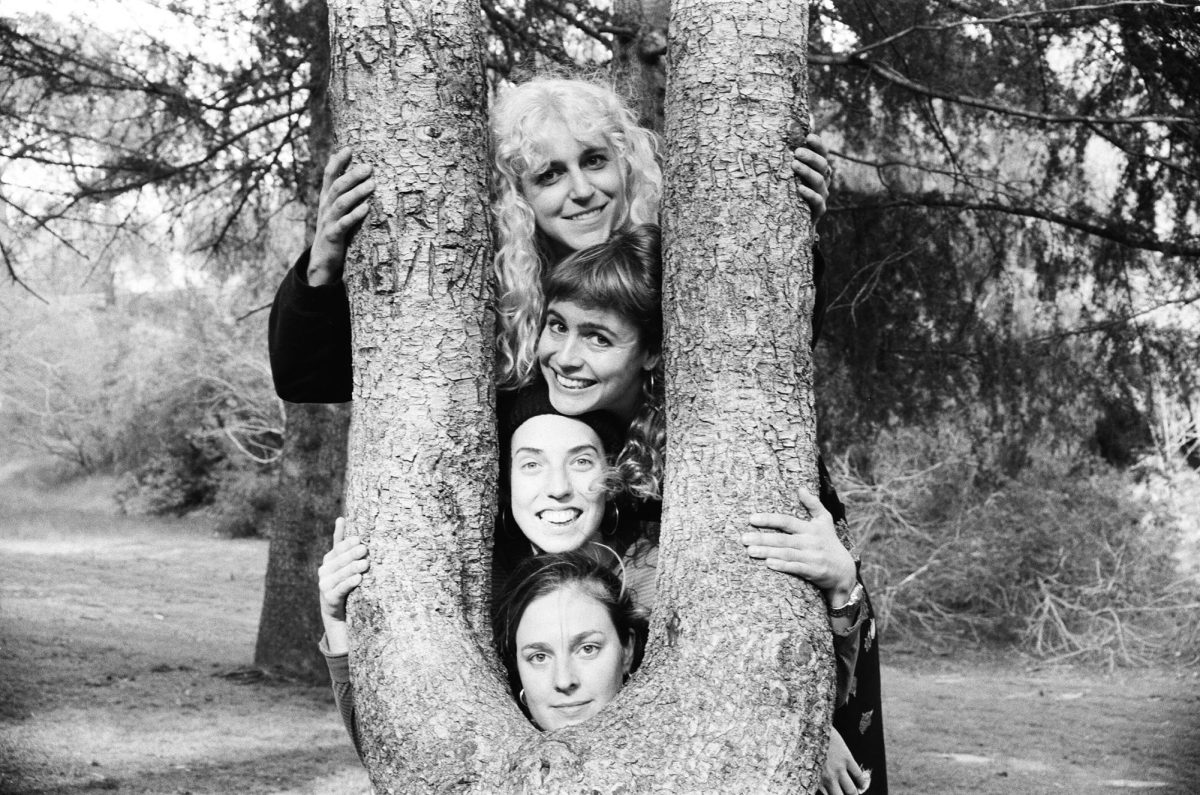

Just under 900 miles away from Kiev, students studying at NYU Prague held a small vigil in Wenceslas Square and the Prague staff raised money for Ukrainians at a bake sale.

Students gathered in two different residence halls to bake and sell treats on Feb. 25. The money was sent to Ukraine for items such as bandages, painkillers, paracetamol and sanitizers.

Filip Chráska, a third-year student at the University of Economics in Prague and RA at Osadni residence hall, spearheaded the bake sale to raise awareness of the crisis in Ukraine and provide assistance.

“It is most importantly shocking that such bloodshed is happening in Europe of 2014,” Chráska said. “I don’t perceive any realistic [threats] for the Czech Republic. For me, the proximity to [Independance Square] rather means a commitment to help.”

Beyond the NYU Prague community, tourists and Czech natives began a small vigil on Feb. 20. They placed flowers, candles and papers with photos of loved ones in Ukraine under the prominent statue of St. Wenceslas.

Gallatin junior Meredith Korda heard about both the bake sale and the vigil, but was not able to attend because of scheduling conflicts. Though she feels safe in the Czech Republic, Korda said her desire to travel to Ukraine was curtailed by the violence.

“It’s really interesting being this close because you definitely hear more about it, and it feels a lot more real,” Korda said. “It doesn’t feel so far away now.”

Korda said she was not surprised by Russia’s military actions, but did find them troublesome.

“The conflict was clearly always about Russia and the European Union to some extent, but I thought they would have kept their involvement more fiscal and behind-the-scenes than [using the] military,” Korda said.

For CAS junior Kelsie Blazier, the social and political upheaval in Eastern Europe was not surprising either — it was almost expected given the recent unrest in the region. As a broadcast journalism major, she wants to involve herself in these events.

“I want to be on the ground with the protesters, taking photographs and filming,” Blazier said. “Now I have the urge to go cover the events because I am so geographically close, and I find the situation at hand both fascinating and frightening.”

Chráska echoed Blazier’s sentiments about feeling a sense of obligation to the situation in Ukraine, despite the distance he said was present among his Czech peers.

“One should feel obligation to any people in need,” Chráska said. “But this very case might [be] more sensitive because the scars of the history of the post-Soviet bloc are still here.”

A version of this article appeared in the Monday, March 3 print edition. Emily Bell is a foreign correspondent. Jordan Melendrez is an editor-at-large. Email them at [email protected].