Paris: Students Volunteer at the Empty Calais Jungle

Although volunteerism is great in its ability to allow people to both explore and better their communities, it can become just a pat on the back for the privileged.

December 6, 2016

Just a train ride from the cosmopolitan centers of London, Paris and Brussels is the Jungle — or what remains of it. A month ago, the refugee camp stationed there was quickly and violently disassembled by French authorities, but a small and fiercely cheerful volunteer hub remains, organizing clothes, preparing food and chopping wood for the camp of displaced refugees.

This is Calais, France. Until recently, refugees coming mostly from Syria, Afghanistan and Somalia came here to escape the terrors of their countries’ leaderships. But because the camp has never been given official status, its existence has followed a troubled trajectory, fraught with food shortages and meager living conditions. On Oct. 26, French authorities declared the camp deconstructed, and when students from NYU Paris and London arrived to volunteer, deconstructed it looked: mud underfoot, and not a trace of the camps that once filled the area — only an immense warehouse and a neighboring woodshed. The camp’s refugees have since been dispersed to other locations across France, but Calais remains a symbolic location for refugee volunteer efforts.

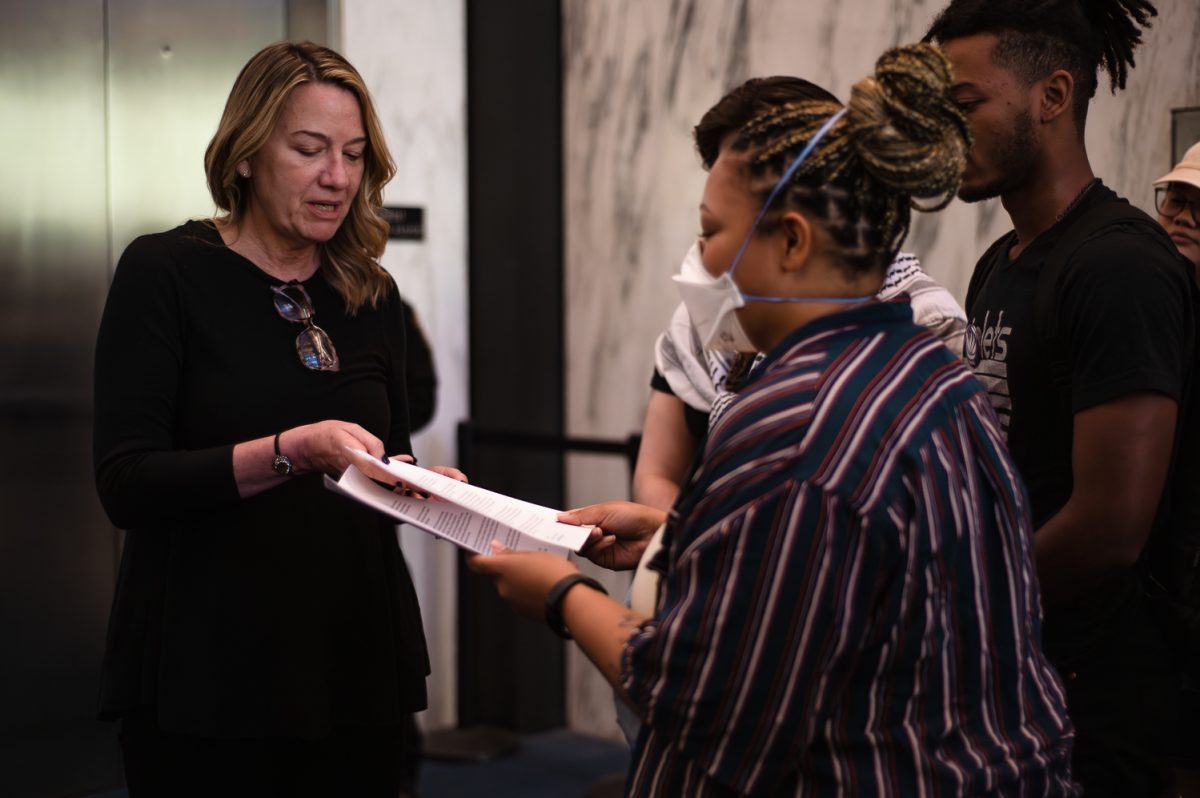

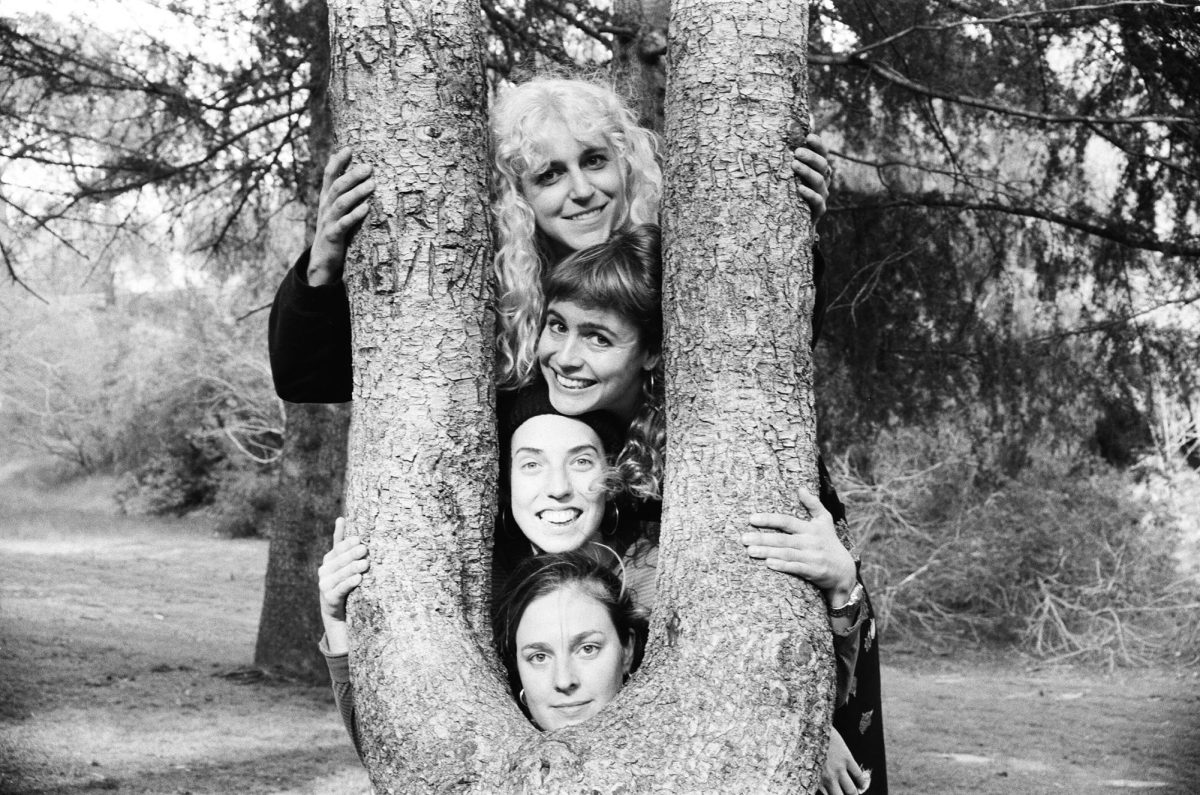

Thirty-six students studying at the NYU Paris and NYU London sites arrived in Calais on the day after Thanksgiving to volunteer, leaving around five hours later. They had the options of working inside the massive warehouse, sorting mountains of clothing, organizing and preparing food or working outside, disassembling wood pallets into their former planks for firewood.

Since July, the camp has allegedly distributed over 132,000 portions of firewood to refugee camps. Firewood gives refugees the freedom to cook what they want when they want, a luxury that camps under strict food rations do not have. According to the Woodyard’s Facebook page, the firewood produced by just five or six volunteers goes to over 1,000 refugees every day. In the camps, refugees don’t have much luxury of choice: meals are composed of tough foods designed to withstand even tougher environments.

Having always been a fan of wooden pallets, I volunteered to work in their deconstruction. “Fire is inspiring,” a volunteer said as he led the group toward the shed. “It’s also necessary, you know, for food, for warmth, heat. It creates a sense of community,” he said. “Plus, using an axe really relieves all those pent-up emotions.”

I had never fully grasped the concept of physical exercise being mental — I was the brief but very dead weight of the ninth grade track team — but when I picked up that crowbar I thought about all the things that make my toes curl, and my handy crowbar gradually (very gradually) turned a pallet into a small pile of boards. That was the first one. Eventually, I found myself easily flinging nail-embedded boards through the air with dangerous joy, gleefully kicking in nails with my shoes. So deluded I was in this euphoria that at one point I exclaimed, “I love physical labor!” And at that awful moment I saw the dangers of privilege, the sociological malfeasances that are revealed whenever one writes about volunteer work. My happiness was exploitative, as is this article. Of course I loved physical labor because I only had to do it for five hours as part of a university-sponsored trip. Some have no choice but to work in manual labor — some are actually exhausted, forced to move from camp to camp in uncertain and dangerous environments.

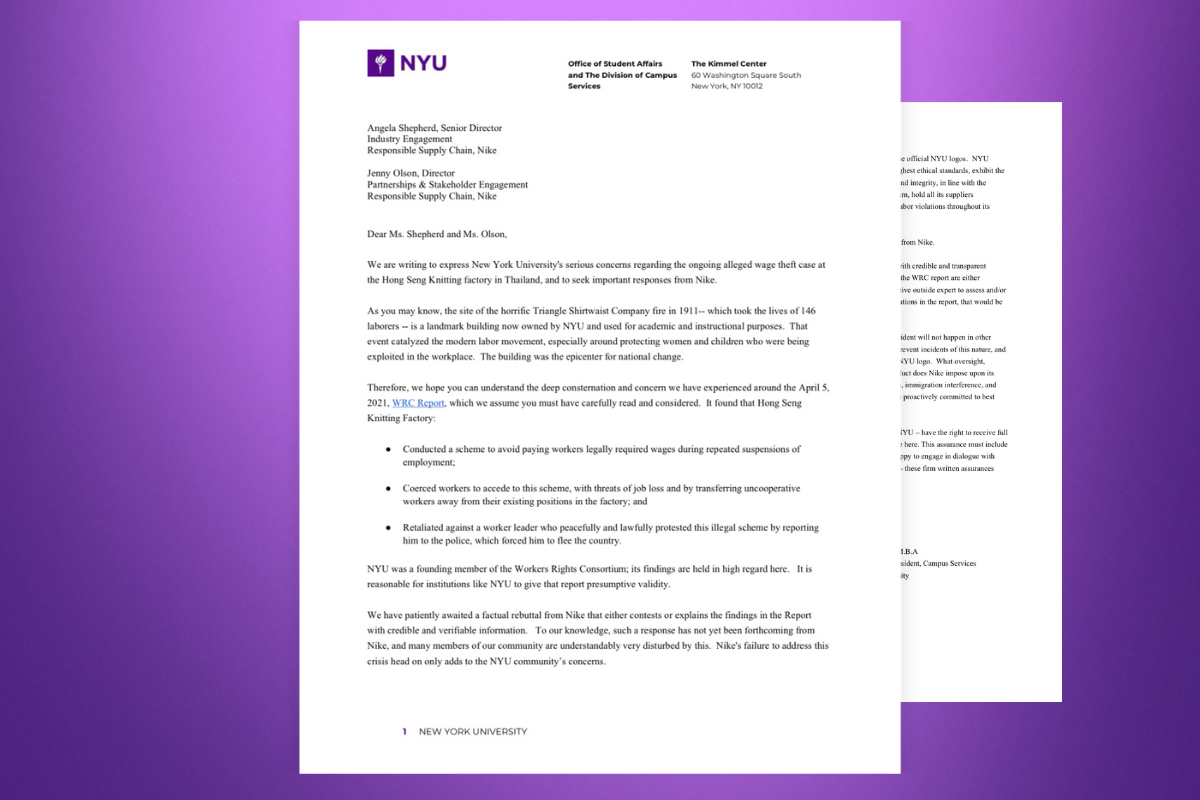

I am glad NYU organized this program because I realize more clearly now that the suffering of refugees is one many are fortunate enough to not know, but must respect. We students were apparitions — well-intended apparitions — but apparitions all the same, with the freedom to leave, the privilege to sleep, later, in a hotel and the ability to dine at multicourse restaurants in Lille, Calais’ wealthy neighboring city. Volunteer work is great. Volunteering is an amazing thing to do. But public displays of volunteerism are too often feel-good projects for the privileged who can use volunteerism as a method of self-betterment; there’s a whole industry built on these pats on the back. Once publicly written about, volunteering becomes a sort of pedestal.

Here’s how you can support a safe future for refugees: Donate money to the Calais kitchens. Support the Calais Woodyard. Support the UK volunteers.

Email Audrey Deng at [email protected].