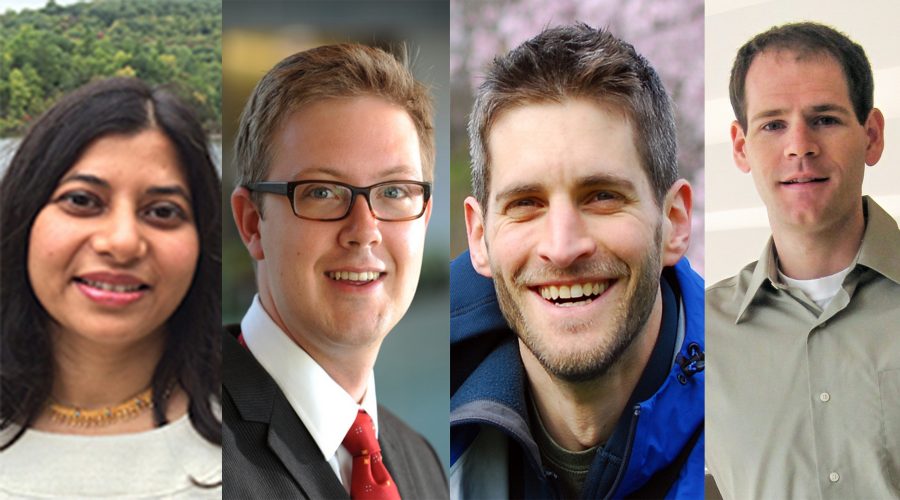

NYU Faculty Among Newest Sloan Fellows

This past week, four faculty members — assistant neuroscience professors Jayeete Basu and Nicolas Tritsch, Stern associate professor Johannes Stroebel and assistant chemistry professor Daniel Turner, were awarded fellowships from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. The 2-year fellowship is given to up-and-coming scientists in various fields.

February 27, 2017

This past week, four NYU faculty members were awarded fellowships from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. The two-year fellowship, given to up-and-coming scientists who have made significant contributions in their field, is awarded to 126 researchers every year. The fellows are nominated by a senior scientist, and the winners are selected by a panel of scholars based on their research, creativity and potential to be a future leader in their field.

The four faculty members — assistant neuroscience professors Jayeete Basu and Nicolas Tritsch, Stern associate professor Johannes Stroebel and assistant chemistry professor Daniel Turner — will each receive a $60,000 prize over a two-year period to further their research. Washington Square News spoke with Basu, Tritsch and Stroebel to discuss their research and award.

Washington Square News: What were some of the key aspects of your research?

Jayeeta Basu: [My team and I] work on two areas of the brain — the entorhinal cortex and the hippocampus. These are two areas that are interconnected. There are long range circuits between these two areas, and these two areas are thought to be critical for the memories of people, faces, objects and events. These are the two major questions we set out to answer — how is information selected from your sensory experiences and encoded as long term memories? And, how does memory shape our ongoing sensory processing?

Nicolas Tritsch: We’re interested in understanding how a part of the brain controls how we produce movement, how we decide which movements to initiate, how those movements are carried out and also how new movements are learned. We are particularly interested in a part of the brain that we call basal ganglia in mammals, and we are particularly interested in a group of cells that releases a chemical called dopamine. We’d like to know what sort of stimuli and conditions engage these neurons, and then once they’re activated, we want to know how they communicate with the cells around them. What we found during my postdoctoral fellowship at Harvard [University] was that those dopamine cells release many more than one chemical transmitter. So, in addition to dopamine, they release large amounts of another chemical called GABA, which is a major inhibitory transmitter in the brain. That is something that had not been noticed or characterized before and it sort of changes how we think of these cells.

Johannes Stroebel: My research aims to understand how households make financial decisions, such as whether to buy a house or borrow using a credit card. In one recent project — for which we collaborated with Facebook — we showed that interactions through social networks affect your home purchasing decisions.

WSN: What is the largest impact of your research?

JB: We know memory shapes experiences — we are going to be able to answer how and where that happens. How and where is as emotionally relevant, behaviorally relevant or memory-related as being added to sensory signals of the brain, and we are looking at two areas of the brain that are affected earliest on in Alzheimer’s. Another thing that I feel our research will help understand is how adaptive learning behaviors are being generated by neural activity in specific circuits. It’s a fundamental question in the field. How do circuit activity [and] neural circuits of neurons produce the behavior of individuals and that would be another impact. A third impact I can see is in the field of epilepsy, where we see a major change in the balance of excitation and the position, and the hippocampus is the focal point of temporal lobe epilepsy.

NT: In Parkinson’s disease, these are the neurons that degenerate and the result is the symptoms of Parkinson’s, which is an impaired ability to move. Movements are slowed [and] muscles are rigid. The fact that these cells release GABA also changes the function of how we think about the brain and also how we think about Parkinson’s disease because now, when these cells degenerate, not only is dopamine missing but in addition the target neurons are no longer under the influence of this inhibitory molecule GABA.

JS: We showed that if your friends live in far-away areas that had recent house price increases, you are more optimistic about housing investments in your own neighborhood and are actually more likely to buy a house.

WSN: What are your future plans in the field, and how do you think the fellowship will affect these plans?

JB: Sloan is an extremely prestigious award, and it also symbolizes how others in the field view the potential of your research. I think one of the biggest things for me was the boost of confidence as an early-stage new investigator. You need to find relevant work. You need to perform work that is direct and shifting that’s novel, and you are typically trained to do only scientific research but you are not trained to run a lab and get grants. All of these things are challenges for new investigators like me, where we had to suddenly step into this role of managing people, managing a big budget, marketing our research and generating funds for our lab. Sloan provides you with the boost of confidence that you’re on the right track — that your research is relevant and has great potential. Right now, I think [the future is] the two projects that I described — the second project where memories shape sensory processing. We want to understand how memories may be modified, how we view certain things and our perception of the outside world — I think that’s the direction our work will be headed to. We will be focusing on that for the next five to 10 years.

NT: The first [effect] is, I think, a boost in confidence. I had to be nominated by a more senior faculty who estimates that there’s some promise in my work. The first thing is an increased sense of confidence that as a young faculty [member] with many questions lying in front of me that I can move forward feeling like I have the support of peers in the field. And that the questions that we have addressed and the questions that we are looking to address are questions that other people in the field agree that are important to look after. It’s first and foremost a validation of this bet or this gamble that we’re making. Of course, it comes with a financial prize as well, and that money will go directly to the support of salaries for graduate students who are going to carry the work as well as some of the reagents that are needed to carry out the experiments.

JS: In follow-up work, I am studying the effects of similar interactions with your social network on a lot of other decisions — from which phone to buy to whether to refinance your mortgage.

Email Arushi Sahay at [email protected]