Experts reflect on Sandy, future planning

Related Stories

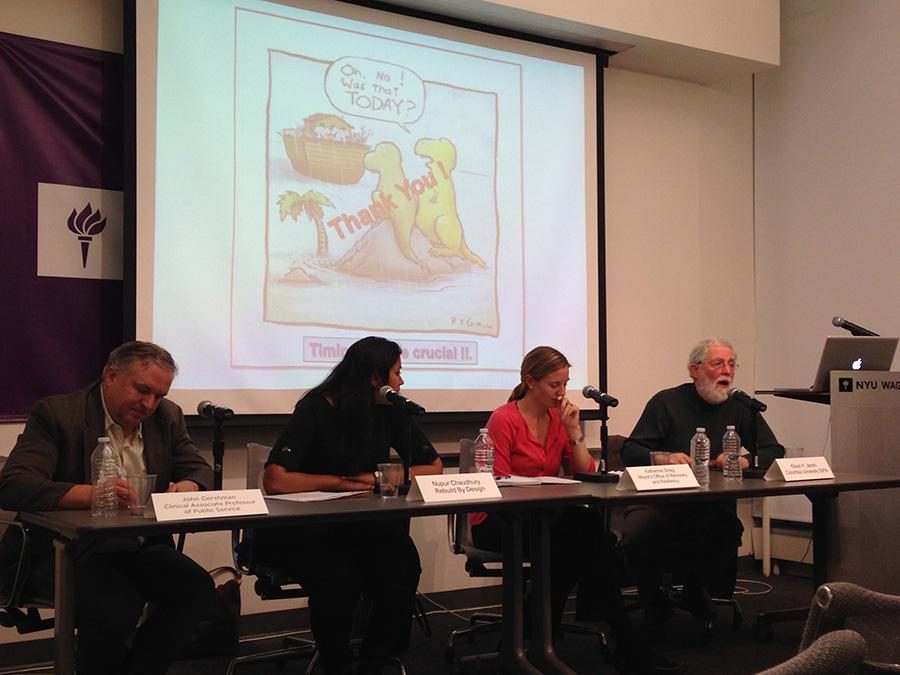

Today marks the two-year anniversary of Superstorm Sandy hitting New York, yet some are not sure the city is entirely prepared to deal with another storm. Klaus Jacob, a professor at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, spoke at NYU’s Robert F. Wagner building on Oct. 28 about disaster preparedness and resiliency in a changing climate. While he cited many examples of positive changes and mitigation projects, Jacob said the city has ultimately fallen short of its goals.

“I think in our attempt to really make a difference in our present situation and economy, we’ve fallen short in finding a long-term solution and resilience,” Jacob said.

The event included a panel discussion with Nupur Chaudhury, senior project manager at Rebuild by Design, and Katherine Greig, senior policy adviser at the New York City Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resilience. The event was moderated by John Gershman, professor of public service.

Jacob said the effects of Hurricane Sandy were as bad as the predictions he and a team of colleagues made a year before Sandy hit: parts of the city flooded within 40 minutes, it took three weeks for infrastructure services to be restored and transportation infrastructure alone sustained $10 billion in damage.

After observing the mitigation measures the city took, however, Jacob said he noticed that there were ways to prevent such disastrous consequences. For example, putting up plywood water barriers and removing sensitive subway signal and control systems were effective forms of damage prevention. Jacob added that the latter method in particular saved the city two weeks of recovery time and billions of dollars after Sandy.

Jacob also said although many plans may collectively benefit the city, people do not want to elevate their homes and reduce their value.

Hannah Kates, Wagner graduate student, said people who do not want to leave homes during times of disaster must be prepared for potential dangers.

“To a certain extent, if people don’t want to leave the area they’re in, that they have to assume some risk that they’re taking on by staying,” Kates said. “The city has to ultimately kind of decide what their stance is going to be regarding this conflict. Like whether they prefer people living in a higher elevation and then having some kind of system in place where the people who decide to stay are assuming the risk on their own.”

Shawn Sippin, Wagner graduate student, said he was surprised by the range of views on the issue.

“I think that, the biggest thing that struck me was the bringing together of three completely different perspectives and creating a dialogue between them,” Sippin said.

A version of this article appeared in the Wednesday, Oct. 29 print edition. Email Christine Wang at [email protected].

Christine is a sophomore in the College of Arts and Science majoring in philosophy and also something that will hopefully make her a living post-graduation....