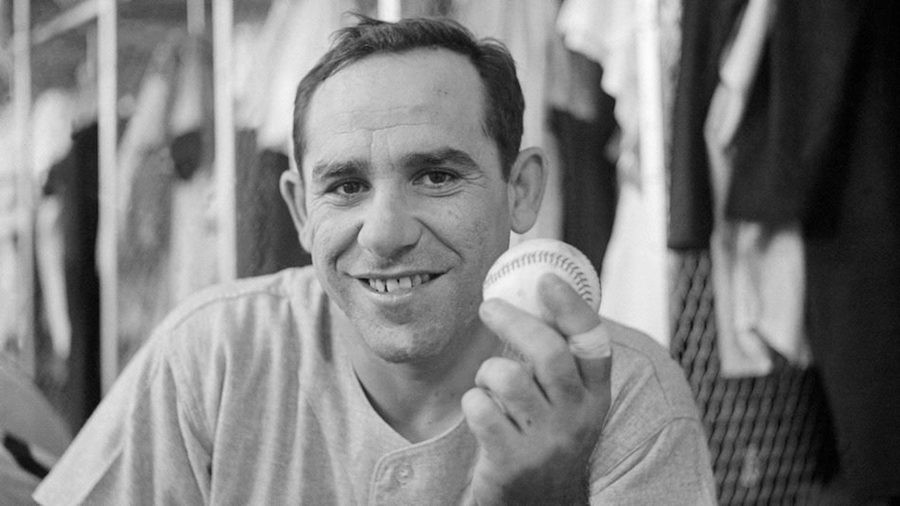

The future without Yogi ‘ain’t what it used to be’

September 24, 2015

On Old Timer’s Day at Yankee Stadium in 2006, Yogi Berra and I had a short conversation that consisted mostly of me shaking.

“I’m a catcher, like you, but only in little league. And I’ve been playing for a while but I’m not that good, not like you.”

He did that ruffle-your-hair-even-though-you’re-wearing-a-hat thing the way dads do, and told me, “Keep at it, no matter what people tell you.”

I stared back at him, wide-eyed. “Definitely. Thank you so much.”

It goes without saying that I looked up to him, and still do.

Early yesterday morning the baseball community was shaken by the news of Yogi Berra’s death at the age of 90. A veteran Yankee of 19 years, his accomplishments are unparalleled. 10 rings as a player, three as a manager, 75 world series games played and countless other achievements earned him the right to be memorialized in Monument Park. Everyone says that Don Larsen’s 1956 perfect game and the hug following it was the moment that immortalized Berra. For me, it was something completely different.

The first time I ever took a catcher’s stance, I pretty much toppled over. My father was ambitious in trying to teach a 7-year-old how to play a position that required a degree of coordination that was foreign to someone like me, who happened to have noodles for legs.

Early in my mediocre Little League career, I found it difficult to pop up and catch the outside pitches that new windmillers were throwing. Being a catcher awarded me the responsibility for both myself, the pitcher and a large part of the game. Tagging runners out at home, lobbing the ball across left field to take out someone tagging up — it was a lot like a meticulous, anxiety-ridden game of chess.

After one particularly rough game with far too many wild pitches and foul balls, I complained to my dad about the impossibility of being a three-foot-tall catcher. He met my complaint with a story of old timers, just as he had nearly every previous time I complained. If Yogi Berra, at a modest 5’7”, could win three major league MVP awards and catch for 10 Yankees World Series titles, then I could certainly handle being the backstop for my little league softball team.

Because of him, I learned to love catching. I realized that it put me at the best vantage point of the game; I found that I was both a spectator and a player.

My dad and I are what I consider the old timers of Old Timers Day. At first, that yearly June game was just me trying to keep track of who was who. Thanks to my dad, I was one of a very few 7-year-olds who could pick Yogi and Larsen out of a crowd. For him, Old Timers Day was a glory game — these were the guys that shaped his father’s years as a fan, and therefore his years too. Sports figures like Yogi are once in a generation. They have the ability to redefine what it means to watch sports, because even though their talent on the field is unmatched, they connect better with people off it.

He was just the way everyone described him, with the kindest eyes you could ever look at, and his face always had a hint of a smile. His quirky one-liners have made him the father of all dad jokes. “You better cut the pizza in four pieces because I’m not hungry enough to eat six,” was a typically quoted phrase around dinner time in my house. He was charismatic both on and off the field.

“It ain’t over till it’s over,” Yogi said. And I don’t think it really is. In baseball, though “you don’t know nothin’,” it’s easy to characterize the end at first glance: nine innings, the last run in extra innings. I don’t think that’s the end though — a series, a season, division title, a career, perhaps even a lifetime — don’t seem to characterize the end for me. Life can be so finite, but it’s players like Yogi who have the ability to impact fans in lifelong ways.

“Love is the most important thing in the world, but baseball is pretty good too,” he said. Maybe he meant love of life, or love for others, or maybe even love of the game — in any case, I couldn’t agree more.

Email Grace Halio at [email protected].