NYU Senior Awarded Rhodes Scholarship for Human Rights

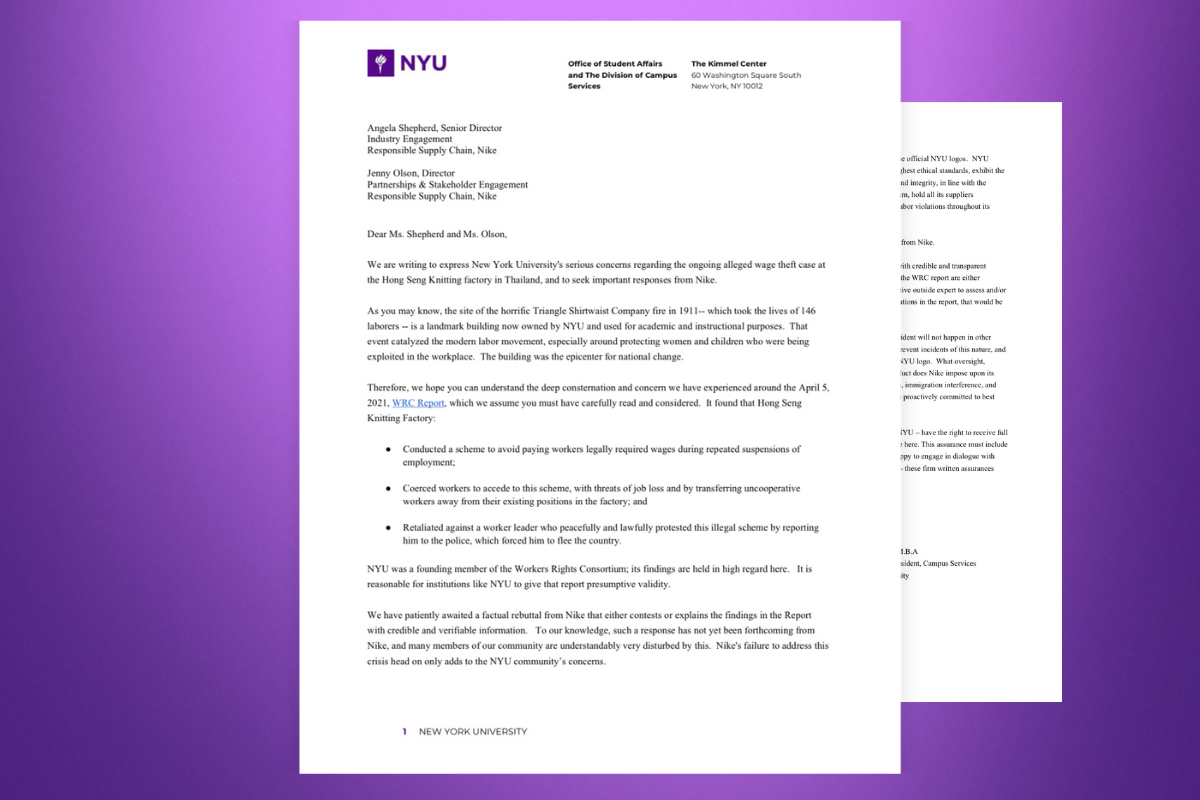

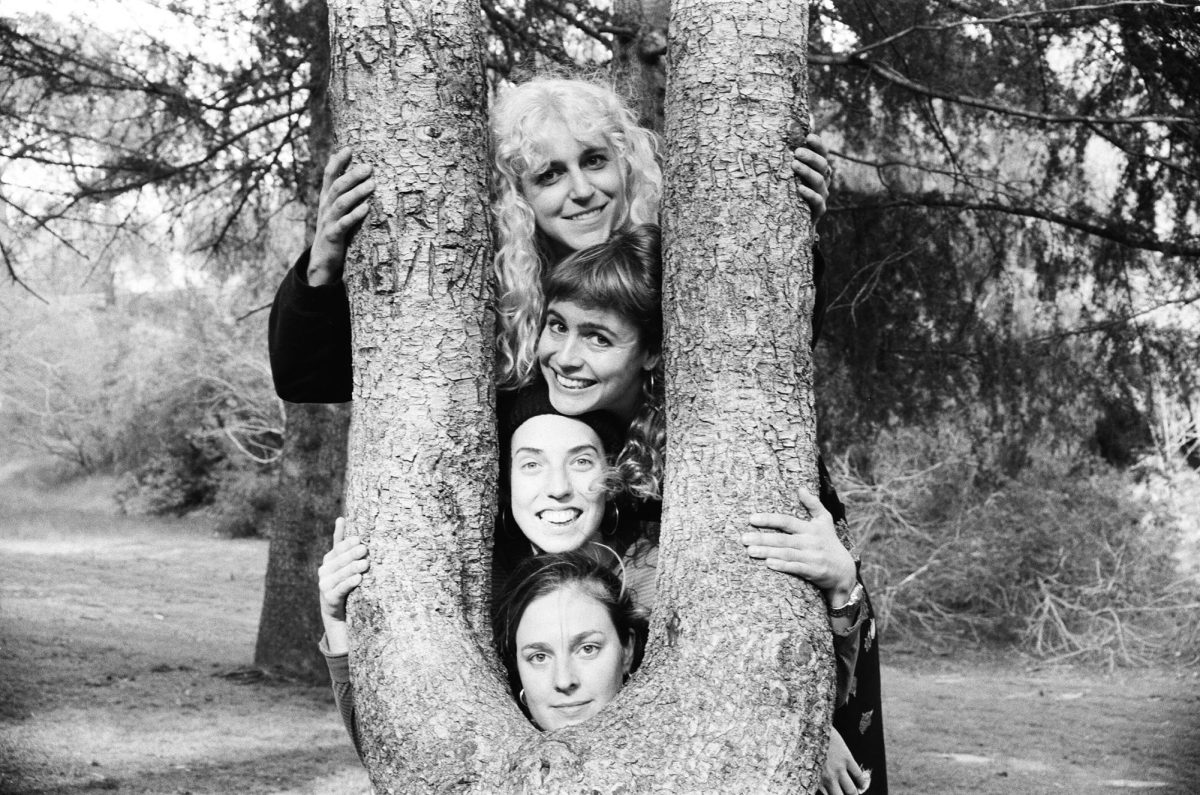

Courtesy of Melissa Godin

GLS senior Melissa Godin is one of three Rhodes Scholars at NYU and has done extensive work in the international community.

November 28, 2016

Not every senior at NYU can say that they’ve interned at the Canadian Embassy, conducted research in Cambodia or served as the head editor for a report on sex trafficking that was then used by the United Nations — but GLS senior Melissa Godin has done all three. She has conducted notable work regarding human trafficking and volunteer tourism, culminating in her receiving a Rhodes Scholarship this year, one of three NYU students to get the honor.

Only 32 students nationwide are chosen to receive the Rhodes Scholarship through an intensive and highly competitive process of applications, interviews and recommendations. Students granted the scholarship receive full financing to attend the University of Oxford for two or three years to continue research without the economic burden.

WSN talked with Godin about the process of applying to become a Rhodes Scholar, the work she has done up until this point and what she hopes to accomplish during her time next year at the University of Oxford.

WSN: Why did you choose NYU?

Melissa Godin: I was kind of debating whether or not I wanted to leave Canada. Canada has some of the best schools in the world and is obviously a lot cheaper than the U.S., but it was actually when I found the program that I’m in now — Global Liberal Studies — that I decided that I wanted to go to NYU because it perfectly combined my academic interests with experiential learning, which was really important for me because I think that interning, studying abroad and doing research is the best way to learn.

WSN: What was the process of getting the Rhodes Scholarship?

MG: It’s a pretty rigorous process, which is why I think that a lot of people, including myself, really debate whether or not they want to apply because it’s just so time consuming. I must’ve spent hours working on my application, six letters of recommendation, an endorsement from the university, a personal statement and then if you do get it you have to fly back to be interviewed. So it’s a pretty big process to put yourself through, but I also think that it was a really valuable one because it forced me to sit down and think about what I wanted, who I was, where I was coming from and where I wanted to go.

WSN: What do you think was the hardest part in applying for the scholarship?

MG: I think it was really easy to prepare academically — to make sure that I read all the news and I was up to date on what was going on in the world — but I think that it was trying to sit down and really think about who I was and what I wanted because those aren’t the kinds of questions that are easy to answer, nor are they the kinds things that we ask ourselves on a regular basis.

WSN: What was the most interesting thing that you learned during this process?

MG: I think that I learned that it’s ok not to have an answer. I think so often with these interviews you feel like you need to provide one answer and one solution and you’re supposed to in there with answers that nobody has ever heard before. I think that I’ve realized that it’s OK to say that you don’t know and that you recognize things are complex and difficult.

WSN: What do you hope to do during your time at Oxford?

MG: I’m going to study the MPhil development studies. Part of that includes field work for your master’s thesis, so I’m thinking about going to Senegal to look at how unconditional cash transfers affect women’s agency. So I’m hoping to have access to these communities through Oxford. I’m also really looking forward to studying in a different country again and studying among some of the best scholars and students in the world.

WSN: What are you plans after Oxford?

MG: The career I hope to pursue is one where I’m part of the research teams that are trying to understand the underlying root causes of poverty because I think that one of the biggest problems in the way the development sector works now is that the underlying root causes are fundamentally misunderstood which in turn leads to representation issues, which consequently leads to solutions being formed that don’t actually address the root problem. What I’m interested in is diagnosing the underlying cause of poverty and finding a way to represent those to audiences in a nuanced way. I’m trying to be a storyteller for development issues.

WSN: Do you have any advice for prospective Rhodes Scholarship applicants?

MG: My best advice is really to go in there and be yourself, and while that it is a simplistic answer that’s ultimately the reason I got the scholarship. I walked into this room and the first person I met had broken through the censorship system set up in North Korea to provide an educational program for youth to teach them about their government, and I’d met other people who were so intelligent in their field and who had medical reports published already. But I think that if I hadn’t anything working to my advantage it was that I was completely myself; I acknowledge my flaws and my weaknesses and I think that ultimately that human quality is something that panelists want to see in learners.

WSN: What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever gotten?

MG: I think that it’s OK to make mistakes would be the best advice I’ve ever gotten. I used to be a figure skater and I can’t tell you the amount of times I messed up my performances or fell on my jumps, but those mistakes really shaped me and formed me as an individual. I think that accepting that you learn the most when you make mistakes would be my best advice for people and would probably be the best advice I’ve gotten.

A version of this article appeared in the Monday, Nov. 28 print edition. Email Jemima McEvoy at [email protected].

donald kibet • Dec 21, 2016 at 8:54 pm

please help me am needy and would like your scholarships,i depend on you ,thank you get me with this number 0720463594

donald kibet • Dec 21, 2016 at 8:51 pm

Iam donald kibet from kenya and would like to apply for your scholarships,contact me throug this number 0720463594