Broadway Legend Baayork Lee Visits Tisch

Baayork Lee hosted and master class and a Q&A at Skirball on September 12th.

September 15, 2017

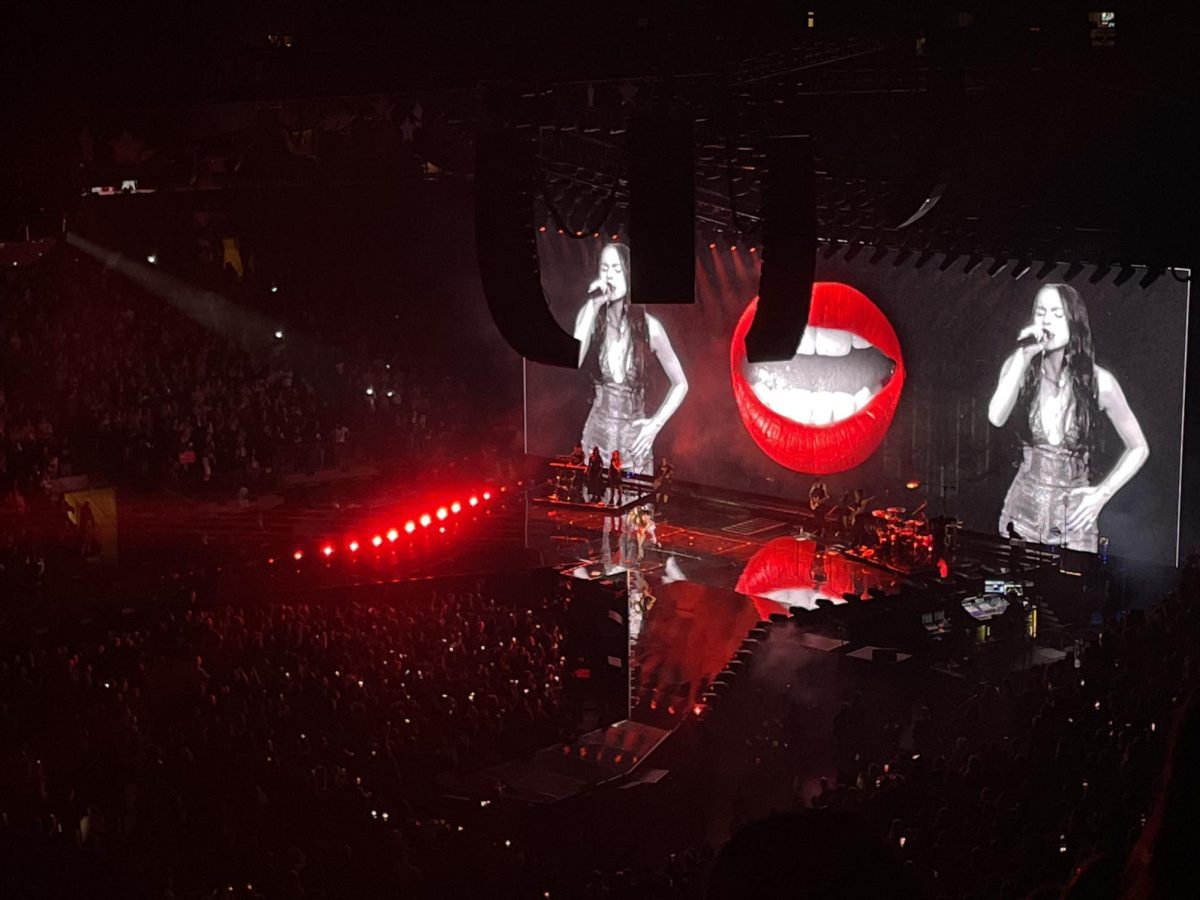

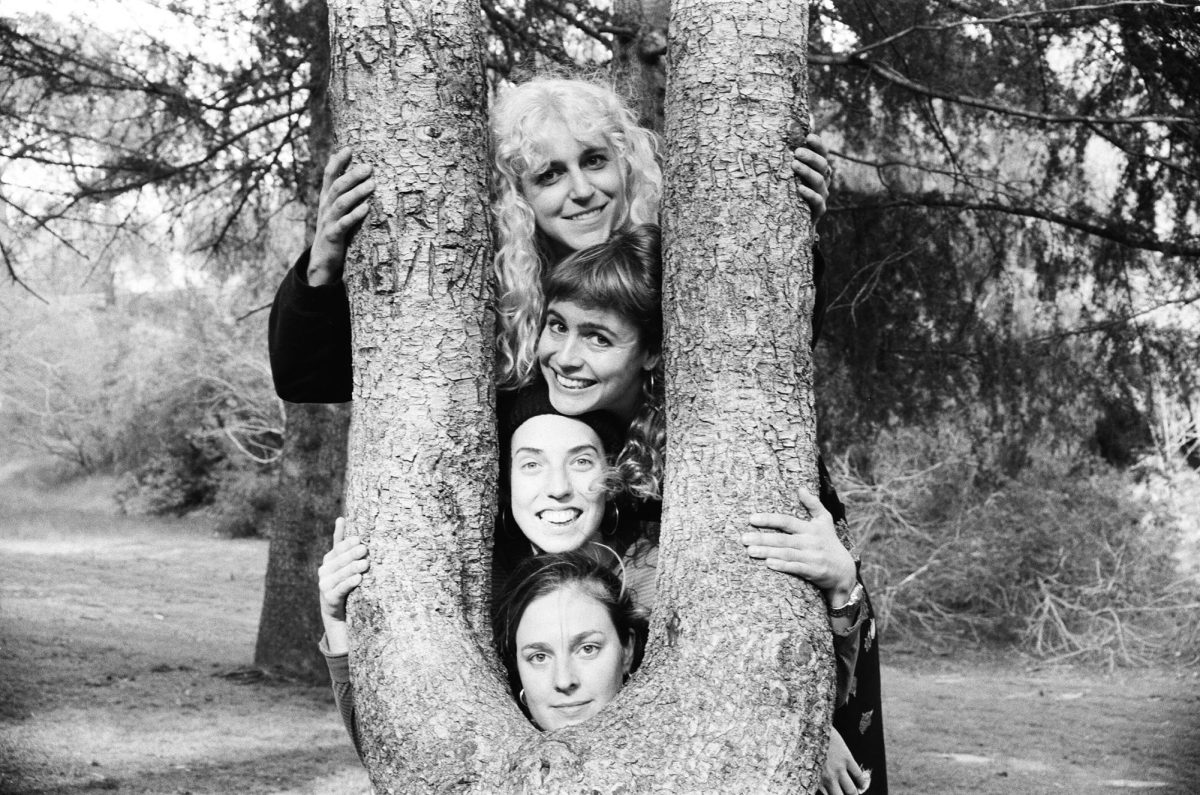

In collaboration with Tisch and the departments of Drama and Dance, Skirball Center for the Performing Arts hosted a masterclass and Q&A on Tuesday night with Broadway legend Baayork Lee. Exploring the seminal works of prolific choreographer and lifelong friend Michael Bennett, Lee coached students in Tony Award-winning choreography from “A Chorus Line” and “Promises, Promises” and spoke on her six-decade-spanning career in the industry.

Born and raised in Chinatown, Lee made her Broadway debut at age five in the original production of “The King and I.” Always the last one picked up at the theater, Lee would dance alone onstage, underneath the ghost light, after performances.

“…And the rest was history,” Lee said. “I knew I had to dance.”

Outgrowing both her role and costume, Lee was fired from the production at age eight, but did not stop there. Soon thereafter, Lee landed roles in a dozen more Broadway productions, including “Rodger and Hammerstein’s Cinderella” and “Jesus Christ Superstar.”

Lee’s breakthrough, however, came when she played Connie Wong in Michael Bennett’s 1975 musical “A Chorus Line.” She subsequently choreographed and directed productions around the world — most notably, the 2006 Tony-nominated Broadway revival. It was her reconstructed “I Hope I Get It” choreography that she taught to Tisch students, yelling “You gotta sing too,” “eat nails” and “from the top. A-five, six, seven, eight.”

“She’s really tough, but she also has this crazy passion that makes you want to be better,” Tisch sophomore Emma Zuber said.

In regards to choreography’s mammoth legacy, Q&A moderators Rubén Polendo, Chair of Drama, and Sean Curran, Chair of Dance, asked, “How do you know when you’re making history?”

Lee responded, “You don’t.”

“A Chorus Line” was revolutionary, featuring an ensemble of diverse dancers from varied races and ethnic backgrounds. The show’s subject matter tackled obscure topics for the time, like cross-dressing, homosexuality and STDs.

“[Michael] made sure there were 17 characters on that stage that were different,” Lee said. “No matter where I am, everyone can relate to these characters.”

When asked, specifically, about equal representation for Asian-American performers today, Lee, Executive Director of the National Asian Artists Project, said there was more work to be done.

“I’m hoping in coming years I won’t have NAAP,” Lee said. “Because [Asian-Americans] will be able to go into an audition, show their talent and get hired.”

For Lee, choreography speaks to all audiences — ethnicity is no barrier. When auditioning dancers, Lee looks for one thing: passion.

“Have passion,” Lee said. “I feel the same passion I felt when I was five years old and saw my first chandelier and red velvet seats…you have to have a fire in your gut. It is not just a job, but a privilege.”

An icon and inspiration, alike, Lee’s fight began, in 1950, for a spot on the F train and continues today with the fight for visibility of Asian-American artists. It was not too long ago when Lee wondered, “Why would anyone care about a short, Asian girl who wants to be a ballet dancer?” And now, in 2017, she is the recipient of the Isabelle Stevenson Tony Award for her tireless efforts in making audiences do just that.

Email Ryan Mikel at [email protected].