Theater of Cruelty Assaults Its Audience

April 5, 2018

The theater is a pleasant place. Showgoers dress up for an evening of glamour, facing star-studded stages from plush velvet seats. At the theater we expect to be treated to reverie. Even boundary-pushing shows only provoke us, with only some leaving a lasting impact on our cognizance.

The theater is rarely uncomfortable. It doesn’t harm or assault us, and we don’t expect to feel fear or uneasiness in the comfort of a Midtown auditorium. Theater of Cruelty — a philosophy and a discipline — is meant to challenge the notion of the theater as an escape to realistic fantasy, convincing us instead of the theater’s role as a crude attacker of the human subconscious.

Antonin Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty began as a challenge. In 1938, writers like Ernest Hemingway and Arthur Miller were crafting plays rooted in concrete language and realism. Artaud yearned for a primal, cruel form of theater that would assault an audience’s senses through sound, lighting, gesture and movement. His publishing of “The Theatre and Its Double” included two manifestos of his Theater of Cruelty, and this movement has emerged with social and political underpinnings since.

Theater of Cruelty is a reversal of Western theater traditions, and according to Tisch professor Andrew Goldberg, a way of drawing out the cruelties and unexpressed, subconscious emotions of everyday life.

“[Artaud desired a form of theater that was] primal, ritualistic, that revealed the true cruelty of everyday life, the fact that at any moment the sky could fall on your head,” Goldberg, who teaches classes in the drama department, said. “He described a hypothetical theatre that assaulted the audience with sound and fury acting directly upon the audience’s nervous system, and [he] likened the theatre to a violent plague.”

Artaud’s book was originally published in French and wasn’t translated until two decades after. Artaud had already died and would not see his work recognized or appreciated. His production of “Les Cenci,” a play about a man who rapes his own daughter and is then murdered, closed after only 17 performances in Paris. But Artaud’s ideas later came to be acknowledged, and many artists went on to produce pieces inspired by his theories.

Despite the social implication behind the Theater of Cruelty movement — that there is a base human instinct to violence and brutality, Artaud did not mean to imply anything political with his ideas. This was not always understood by his later admirers, such as Jean Genet and Peter Brook.

While Artaud did not produce many plays that reflected his ideas about Theater of Cruelty during his lifetime, political theater groups such as the Living Theatre have used the philosophies attached to Theater of Cruelty to create political pieces.

“[They] were inspired by Artaud to create visceral, environmental, ritualistic, non-conformist theatre,” Goldberg said. “In some cases this was a misreading of Artaud, who did not relate his theatre to political ends. Some interesting recent scholarship has [even] seen proto-fascist tendencies in Artaud’s assaultive version of theater that forces the audience to submit to his vision.”

The social implications of Artaud’s philosophy may be showing themselves in modern politics, but the discipline of Theater of Cruelty has not completely surfaced in today’s art.

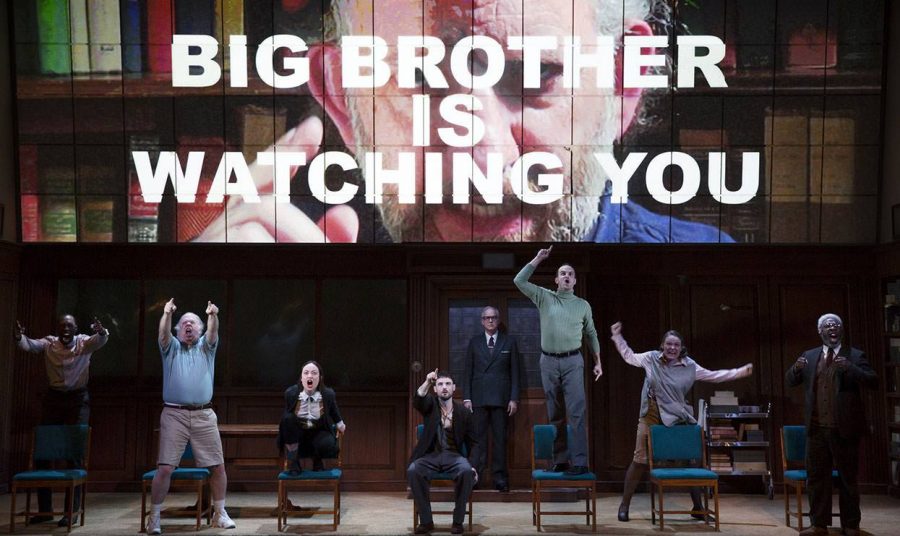

Art today still keeps us comfortable — consider the recent Broadway openings of “Frozen,” “Mean Girls” and “Anastasia.” Even boundary-pushing productions don’t quite fall into Artaud’s desired realm. The most recent Broadway production of “1984,” featuring Olivia Wilde and Reed Birney, was both lauded and attacked for its PG-13 torture scenes, blackouts and sudden jackhammer sounds.

Although this production came close to the Theater of Cruelty genre, Artaud once imagined the audience sitting in the middle of the theater while performers moved around them. “1984” did not approach that level of disruption and is thus not truly a modern example of this movement.

“1984 was certainly graphic and violent, but I’m not entirely sure that is the same thing as cruel,” Goldberg said, emphasizing Artaud’s philosophy of Theater of Cruelty as opposed to the actual discipline of the movement. “The cruelty that Artaud was getting at is not just a literal shock of blood and guts, it’s the much more horrible idea of the cruelty of the universe, an awareness of human suffering.”

Theater certainly tries to make us more aware by revealing human truths, but the violent truths of Theater of Cruelty and the ways Artaud imagined them to be portrayed have not yet reached the Great White Way.

A version of this article appeared in the Thursday, April 5 print edition. Email Emily Fagel at [email protected].