The Atomic Age of Anime

April 5, 2018

The decimation of Hiroshima and Nagaski is known throughout the world today as one of the most brutal and pivotal movements of World War II. But what few people care to investigate is how manga and its offspring – anime – allowed for the healing process in Japan to manifest in artistic, cathartic, everlasting forms.

People started to look for ways to deal with the trauma after the war came to a close. There was a divergence between how Japan recovered through honest yet fictionalized portrayals of the destruction of nature, the inefficiency of war and mankind’s resilience against the two, while American artists put on their rose-colored lenses and produced multitudes of comic book series based on normies-turned-heroes by the power of nuclear waste or outlandish science.

Japanese artists developed a way to heal with distinct creativity and artfulness. Osamu Tezuka authored the “Mighty Atom” series (or as it’s known in the United States, “Mega Man”), which explores Japanese disdain with the United States’ failure to apologize for the bombings — as well as man’s abuse of technology. Other series like “Barefoot Gen” and “Struck by Black Rain” attempted to externalize the sorrow Japanese citizens felt about the destruction of their environment and the fear inflicted upon their society. But these cartoons also reinforced that Japan would see its resurrection in the decades after the war through perseverance over all obstacles.

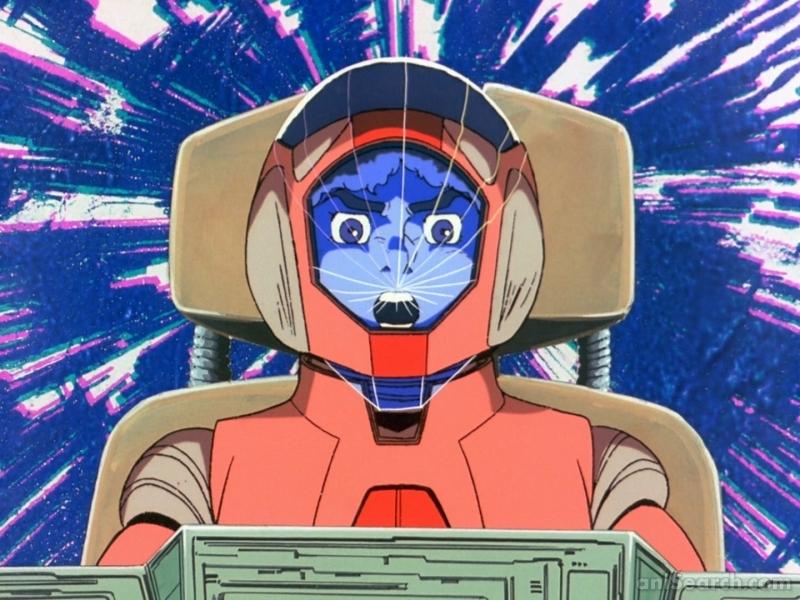

Comic book artists continued producing anti-war content in Japan, eventually birthing the mecha genre. From the gray pages of literature to the nascent silver screens, manga found a new home in the movies. The mecha genre is defined by larger-than-life sci-fi monster battles – think Godzilla – that all attempted to demonstrate the chaos precipitated by the abuse of technology and nature. Content creators were galvanized by the horrors of war, which to them seemed antithetical to peace itself.

Certainly, no one is arguing that anime and manga would not have existed had the tribulation of war not struck the Japanese.

“The literature was already firmly established before World War II; however, it may look very different without the advent of ‘Astro Boy’ or other manga from the time,” said Chris Kincaid, a writer for Japan Powered, a forum for Japanese culture. “Godzilla would not have existed in his current form as well. It is possible that the mecha genre and others would have less focus on nuclear-like destruction and armaments.”

Even after the age of anti-war literature founders like Tezuka and “Mega Man,” the movement prevailed in the soon-to-be-legend Hayao Miyazaki. That’s right. The man who gave us the wondrous and eternal masterpiece, “Spirited Away,” started out in the anime world creating films that illustrated the same denouncement of war. Movies he oversaw the production of like “Kiki’s Delivery Service” and “Howl’s Moving Castle” all have resilient and brilliant young girls as leads because Miyazaki saw how many children had been orphaned by the war and left to fend for themselves.

Then, with the rise of television cartoons in the 1970s and 1980s, anime found a new home in the American theater. Shows like “Sailor Moon” and “Pokémon” were wildly popular with American youth, and the dissemination of anime has only grown since then.

Why, though? In an article by The Artifice, the rise of anime is being attributed to greater accessibility thanks to innovative streaming services like Crunchyroll, the at times strikingly different behavior of characters in anime – reflective of non-Western sensibilities and a desire to explore themes rarely visited by shows targeted at young adults — like homosexuality and violence — in a way that isn’t childish or aesthetically sterile.

“I think that the content of anime is a lot different from Western shows —Western shows really focus on shock value and sex appeal and romance as their defining characteristics,” Tandon first-year Melanie Triplett said. “[Anime] still has those things [but] I found that a lot of the time, anime has really intricate plots that are really fun to follow. And the episodes are usually 20 minutes so you can easily binge watch 15 or 20 in a day.”

Anime and manga combine pleasing visuals with content and plotlines that actually mean something to their audiences. The beauty of anime is that it is rendered limitless by its cartoon nature, and animators continue to abide by their desires to construct stories that explore the range of human emotion and experience.

And considering the current administration, it’s really no wonder why anime has been embraced with unprecedented ubiquity in the West. American youth are looking for a change both in their government and in the popular culture they enjoy. There is now a collective desire to see cartoons utilize their near-infinite potential to illustrate experiences as they are in the real world, wrapped up in artistry and magic.

A version of this article appeared in the Thursday, April 5 print edition. Email Alejandro Villa Vásquez at [email protected].